The Visionaries Behind the Original Miata

This is the inside story of how a lightweight roadster survived boardroom doubt, prototype dead-ends, and safety-era compromises to deliver pure driving joy. The pivotal pitches, the “must-stay-light” fights, and the moment the first prototype finally felt like horse-and-rider as one.

Two very different paths, one from a journalist’s chalkboard sketch, the other from a designer’s eye for timeless proportion, collided inside Mazda and gave the world the NA Miata.

The Chalkboard That Started It

Everything started in a conference room in Hiroshima, spring 1979. Bob Hall, then an American auto journalist who spoke fluent Japanese and knew Mazda’s history inside out, picked up a piece of chalk and drew what car enthusiasts were missing: a simple, front-engine, rear-drive roadster that revived the spirit of the classic British two-seater, minus the leaks, the electrical gremlins, and the unreliability. It wasn’t a styling sketch; it was a product brief. Light weight. Affordable. Open top. Rear-drive. Everyday dependable. The idea landed with R&D chief Kenichi Yamamoto, who had a soft spot for big bets that made Mazda feel different.

From “What If?” to Reality.

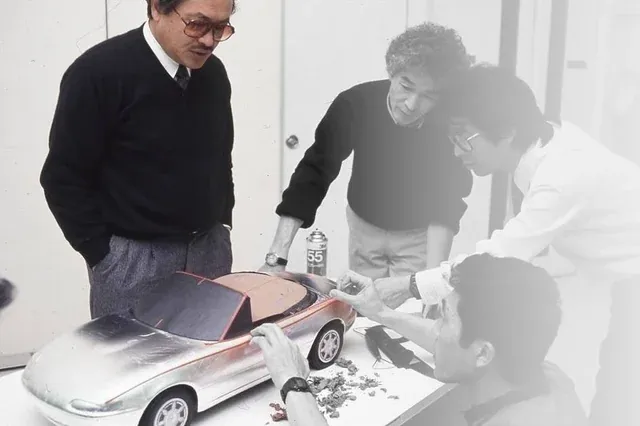

Hall joined Mazda’s U.S. R&D in the early ’80s and kept working the idea from the inside. He and a small crew put numbers to the dream: packaging studies, parts bins worth raiding, and a price target that wouldn’t scare the accountants. To visualize the proportions and stance, he brought in C. Mark Jordan to help sketch the “Lightweight Sports” concept the way drivers would actually see it in the wild, low cowl, clean fenders, thin pillars, wheels that filled the arches. The point wasn’t nostalgia; it was to bottle the feeling of a light, honest sports car and deliver it with modern reliability.

Two Studios, Three Directions.

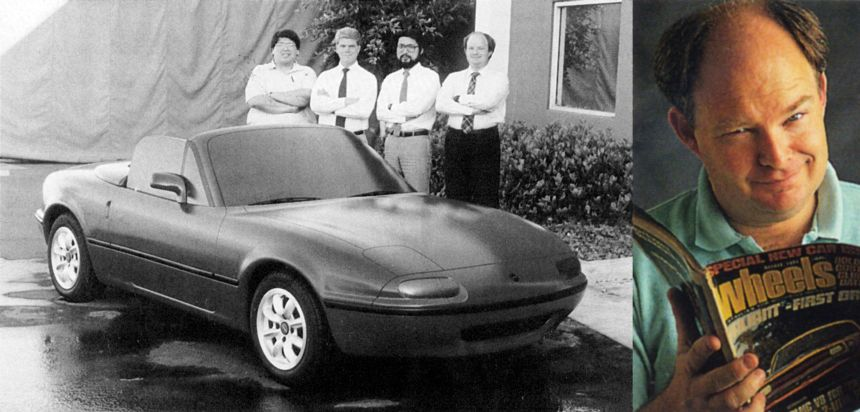

Mazda set up a contest. Tokyo explored two ideas: a front and a mid-engine coupe. The American studio pushed the front-engine, rear-drive convertible. Each camp built full-scale models. Judges picked the American proposal, twice. The convertible felt the most “lightweight sports” in the way you and I define it: roof down, horizon in your lap, chassis talking back in full sentences.

The Santa Barbara Road Test

To prove the concept beyond a design clinic, Mazda hired a British firm to build a running prototype, code-named V705. It looked rough but drove like the brief promised. The team shipped it to California, slipped it onto public roads around Santa Barbara, and watched people react. Heads turned. Thumbs went up. Drivers smiled at stoplights. That real-world test did what slide decks can’t, it made the business case feel obvious.

Green Light and a North Star

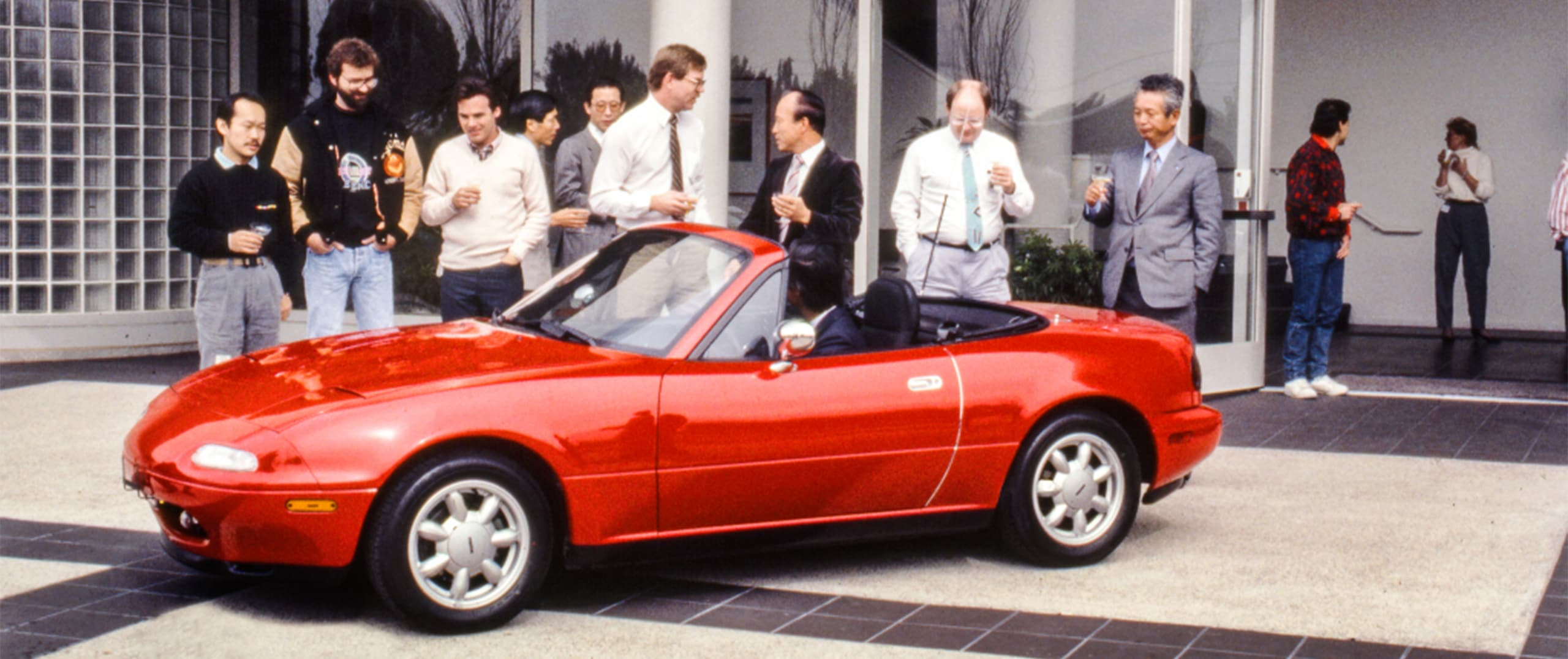

With momentum on their side, Mazda’s board approved the program. Toshihiko Hirai took over as program manager and gave the team a mantra: Jinba Ittai, horse and rider as one. That phrase became a checklist for every decision. Keep weight down. Set the engine back for balance. Use double-wishbones at all four corners. Aim for near-perfect weight distribution. Put the controls where your hands and feet expect them. Build a soft top you can raise or lower with one hand at a stoplight. Through a Los Angeles design clinic and months of surfacing work, the car’s look tightened up until the team froze the design in September 1987.

Bob Hall: The Instigator and Shepherd

Hall didn’t “style” the Miata; he made it possible. He framed the mission with guardrails that kept the car honest: rear-drive, open-top, light, affordable, reliable. He kept senior leadership interested when safer ideas (like FF coupes) seemed easier to defend. He partnered with designers early so the package looked right from across a parking lot and felt right behind the wheel. And he fought for usability details, the one-hand top, the driving position, that transform a neat idea into a car you love to live with. If you’re telling this as a character piece, Hall is the spark who wouldn’t let the spark go out.

Tom Matano: The Designer Who Made “Friendly” Timeless

Tom Matano arrived with a deep global résumé and the instincts of a designer who knows when a line is trying too hard. Under his leadership on the American side, the team tuned stance, surfacing, and that unmistakable Miata “face” until it read as friendly in your peripheral vision, inviting, not cutesy; classic, not cosplay. Matano worked shoulder-to-shoulder with C. Mark Jordan, Wu-Huang Chin, and Masao Yagi through several full-size clays to get the tensions right: simple volumes, crisp fender peaks, a beltline that makes the cockpit feel open. Once the U.S. theme won, Hiroshima’s studio, with Shunji Tanaka as chief designer for the production NA, refined the body and developed an interior that matched the car’s friendly honesty. The baton pass held: the production car kept the intent intact.

Why the FR Roadster Won

On paper, the front-drive and mid-engine paths had advantages: parts commonality, packaging tricks, flash. But the convertible roadster solved the brief without qualifiers. It felt light because it was light. It felt connected because the geometry put you in the right place relative to the front axle and the car’s roll centers. And it telegraphed joy at a glance. When Mazda compared the proposals in 1984, the verdict wasn’t a rejection of the other teams’ work, it was a recognition that the simplest answer was the right one.

Turning Philosophy Into Hardware

“Jinba Ittai” is a beautiful phrase; it also forced hard choices. The team chased low mass through every system. The engine sat back toward the firewall for better balance and steering feel. Double-wishbone suspensions gave engineers freedom to control camber as the car rolled, which kept the contact patches happy without resorting to band-aid tires. The shifter and pedals landed where your limbs wanted them. Sound-deadening was used thoughtfully, never to smother feedback. And that roof? It was engineered like a habit, one latch, one motion, job done.

The Crew That Made It Real

No one person “made” the Miata. Kenichi Yamamoto created the culture that let a small idea grow. C. Mark Jordan shaped the early proportions and packaging that sold people in the first five seconds. Wu-Huang Chin and Masao Yagi tightened the exterior theme when every millimeter mattered. Shunji Tanaka guided the production car’s look and cabin so it felt as honest inside as it looked outside. Norman Garrett and the U.S. engineering team made sure the paper package felt cohesive on the road, and quietly laid groundwork for the spec-racing explosion the car would inspire. And at the center of the web, Toshihiko Hirai kept the team’s eyes on the north star.

Design Freeze, Chicago Debut, and What Happened Next

With the design frozen in late 1987 and the engineering converging on target, Mazda chose a big stage for the reveal: Chicago, February 9, 1989. The press reaction was instant, but the real proof came from buyers who’d been waiting years for something this pure to come back around. The Miata kicked off a full-blown roadster renaissance, validated a product plan that once looked risky, and started a lineage that would become the world’s best-selling two-seat sports-car family.

Why the Miata STILL is the Answer

Plenty of cars are faster. A few are lighter. But the Miata’s trick is how the pieces meet in your hands. You don’t have to be at ten-tenths to feel it doing its thing. The steering talks. The body moves honestly. The car rewards the basics, vision, line choice, smooth inputs, so every mile is practice you actually want to do. That’s Hall’s mission made physical, and Matano’s sense of proportion made visible.

The NA Miata didn’t happen by accident. It happened because a journalist-turned-planner wrote a brief that never blinked, a designer shaped that brief into a form you still recognize at a glance, and a cross-Pacific team kept the intent intact from chalkboard to clay to showroom. The result is simple to describe and hard to copy: a car that makes you feel like a better driver the second you pull out of the driveway.

The Miata community often credits the car’s lasting appeal to the blend of clear product vision and timeless design discipline. Remember Tom Matano for the restraint that made the NA feel friendly without going retro, and remember Bob Hall for insisting the mission never lose its center. The car’s DNA, light, honest, joyful, remains their shared legacy.