The Story Behind the Miata’s “Jinba Ittai” Philosophy

Mazda built the Miata on the ancient concept of jinba ittai—“horse and rider as one.” InEvery Miata is engineered to feel like an extension of the driver, a harmony of balance, feedback, and connection that defines Mazda’s DNA.

Picture a mounted archer thundering past wooden targets at Kamakura’s Tsurugaoka Hachimangū, releasing three arrows in a few heartbeats, horse and human moving like one organism. Mazda lifted that ideal, jinba ittai, “horse and rider as one”, and built the Miata around it. This isn’t just a pretty phrase. It’s an engineered, testable feeling that shaped the MX-5 and, eventually, the way modern Mazdas are made.

What It Means

Literally, jinba ittai combines “person,” “horse,” and “as one body.” The idea comes from yabusame, a Kamakura-period ritual of mounted archery where the archer hits three targets at speed. The point is total synchronization, mind, body, and movement aligning under pressure. Mazda’s definition maps that unity to driving: the car should behave like an extension of your body. If you want the quick guide, say it like this: “jeen-bah it-tie.”

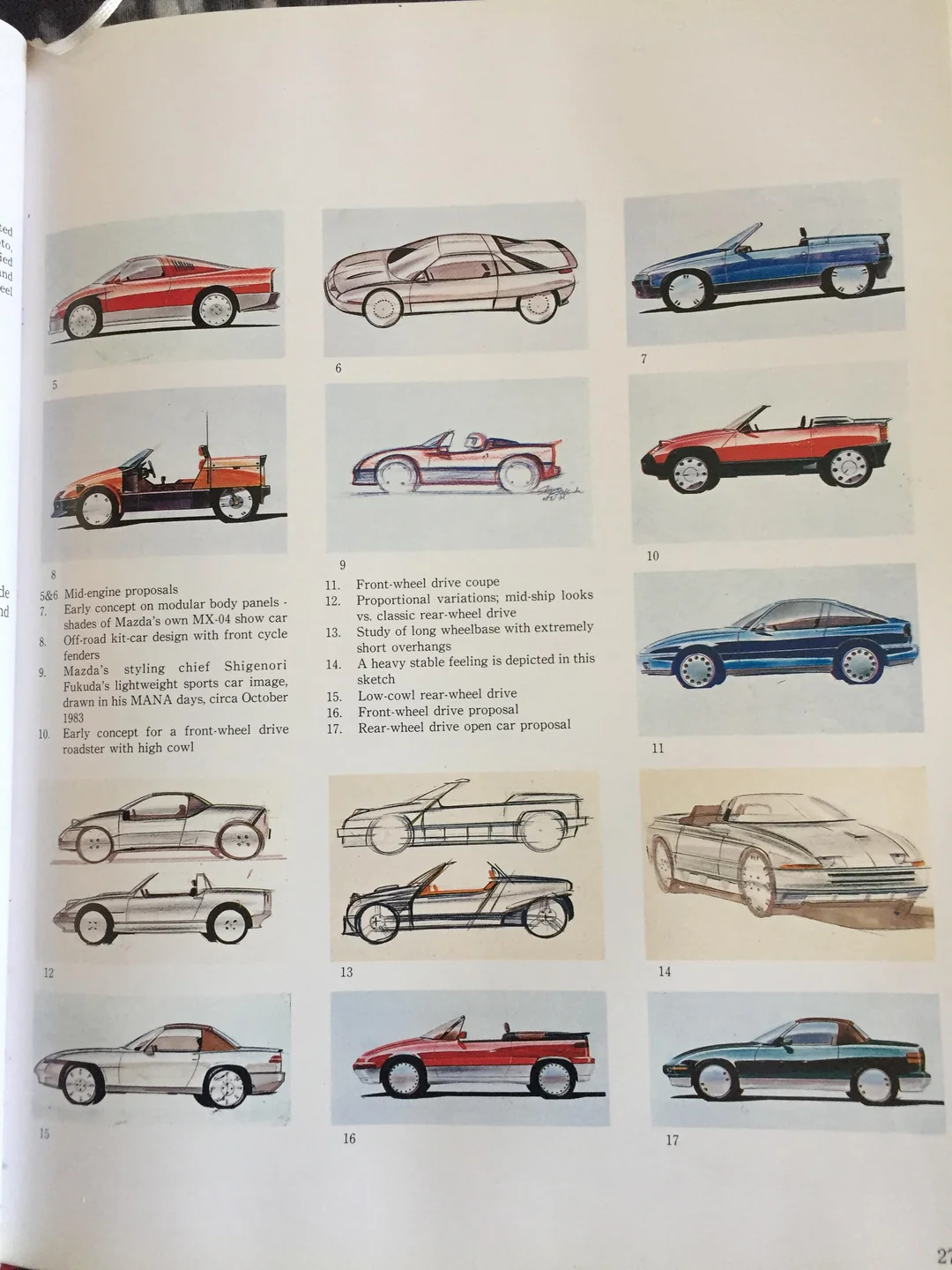

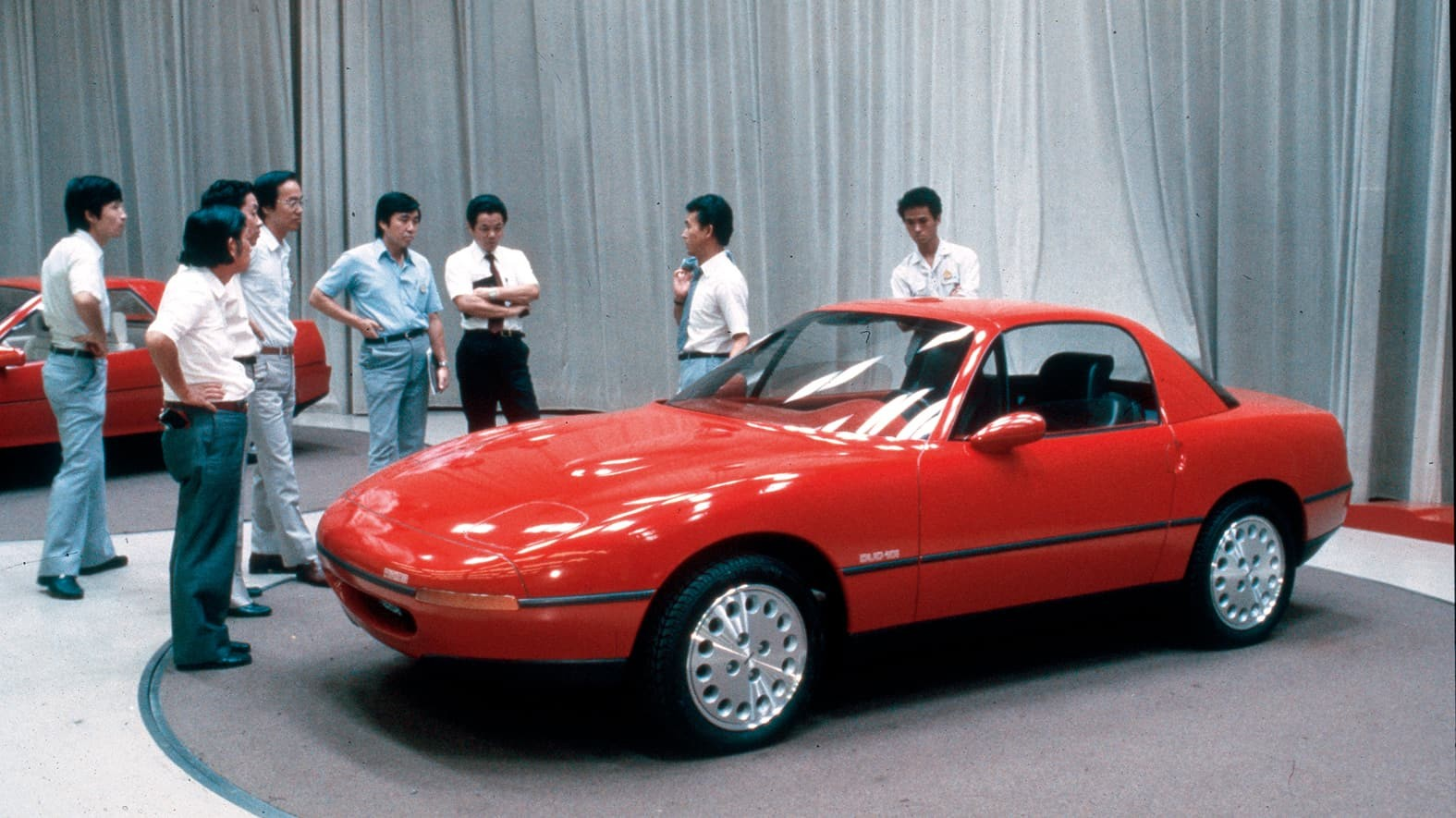

From Concept to Reality

The Miata’s origin story starts in 1979 when journalist Bob Hall sketched a lightweight roadster concept for Mazda’s Kenichi Yamamoto. The seed took, and by the mid-’80s Mazda had turned the sketch into a mission. When Toshihiko Hirai became program manager in 1986, he set the non-negotiables: keep it light, front-mid engine placement for balance, double-wishbone suspension, a quick manual soft top, and jinba ittai as the dynamic north star. The production car hit the spotlight at the 1989 Chicago Auto Show and promptly rewired what a modern roadster could be.

Engineering the Feeling

Mazda turned poetry into physics by starting with the human and packaging the car around that. Seating position stabilizes your vision; the floor-hinged “organ” accelerator lets your heel rest so your foot and the pedal move together with less effort; sightlines, pedal spacing, and steering reach are tuned to reduce strain and micro-corrections. Balance is treated as a tool, not a trophy, near 50:50 weight distribution supports linear, predictable reactions so the car answers your inputs without lag. Then there’s the “gram strategy,” where engineers chase grams instead of kilos: more aluminum and ultra-high-tensile steel, thinner seat structures, a lighter soft top, dozens of tiny cuts that add up. A signature Miata piece ties it together: the Power Plant Frame, a rigid link between transmission and differential that preserves that “one-piece” response you feel through the shifter and rear axle.

Generations Through the Lens

The NA (1989–1997) is the template: featherweight, double wishbones all around, a flip-fast soft top, and steering that talks back in full sentences. The NB (1998–2005) refines the same recipe with a stiffer shell and a bit more power without losing the mission. The NC (2006–2015) grows up, more space, retractable hardtop era, yet keeps the directness via careful tuning and that ever-present PPF. The ND (2016–present) swings the pendulum back to lightness with the gram strategy, then layers in smart software: in 2022, Kinematic Posture Control subtly brushes the inside-rear brake in hard corners to calm roll and make steering feel more linear, all with zero added hardware or weight. For 2024/2025, the Asymmetric LSD (on manual Club/GT trims) uses different ramp angles on accel/decel to steady yaw, while revised steering reduces friction for cleaner feedback. It’s “oneness” by calibration, not just parts.

Beyond the Miata

Mazda scaled the same philosophy across the lineup. The company’s human-centric development playbook aims for effortless control and relaxed confidence whether you’re in an MX-5 or a CX-5. SKYACTIV-Vehicle Dynamics tools like G-Vectoring Control quietly trim torque (and, in GVC Plus, add a touch of braking) to smooth load transfer so the car feels like it’s reading your intent. The point isn’t to layer on tech, it’s to make the tech disappear into feel.

Design That Matches the Drive

KODO, “Soul of Motion”, is the visual partner to jinba ittai. Surfaces are sculpted to look alive at rest, using light and shadow instead of busy lines. Beneath that is Kansei engineering: the belief, championed by Yamamoto and carried into the MX-5 brief by Hirai, that cars must connect through the senses first. The clay, the metal, the switch resistance, the way the wheel returns to center, it all aims at the same emotional target.

Measuring “Oneness”

Mazda treats “feel” like a spec. Engineers chase linear steering around center, reduce latency between your inputs and the chassis response, and manage load transfer so small corrections feel natural instead of twitchy. Posture and vision stability are measured, too: seat height, pedal arcs, and wheel reach are tuned so your pelvis stays upright and your head stays steady, which lowers fatigue and improves precision. The famous 50:50 balance demo is just the foundation; the magic is in the damping, bushings, and software that sit on top of that neutral platform.

Misconceptions

“Jinba ittai is just marketing.” If it were, Mazda wouldn’t have spent decades aligning hardware, software, and ergonomics to achieve the same driving sensation across four generations. “Miata is simple, so it’s unsophisticated.” Simplicity is the goal; the sophistication is hidden so the car feels simple. The gram strategy and selective tech like KPC and GVC are proof.

The Road Ahead

Mazda’s stance is clear: the human-machine bond remains the priority no matter the powertrain. Whether the torque comes from pistons or electrons, the brief doesn’t change, design the car so it moves with you, not next to you. That’s jinba ittai, and it’s the through-line from a thundering horse lane in Kamakura to the smallest sports car in your driveway.